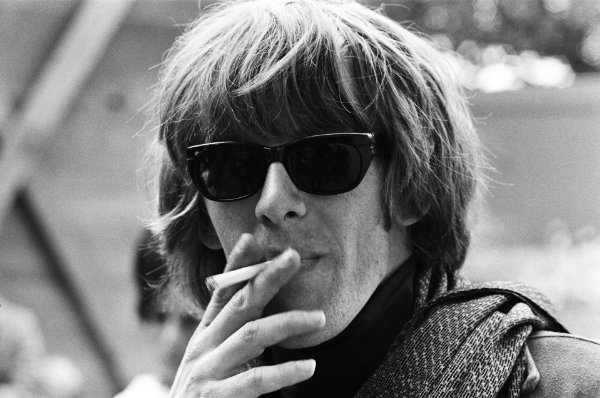

My indelible image of Paul Kantner, the bespectacled, bookish co-pilot behind rock’s psychedelic Jefferson Airplane, who died Thursday at 74, was not in the footage from Woodstock or Altamont or even the great playing on the 1968 live album “Bless Its Pointed Little Head.”

My indelible image of Paul Kantner, the bespectacled, bookish co-pilot behind rock’s psychedelic Jefferson Airplane, who died Thursday at 74, was not in the footage from Woodstock or Altamont or even the great playing on the 1968 live album “Bless Its Pointed Little Head.”

It was at a restaurant lounge in suburban Avon, Connecticut in late 1998, where his version of the Jefferson Starship were playing an encore of the brash, insurrectionist “Volunteers” that, vital as it still was, couldn’t get diners to put down their forks in the rear of the dining room.

Surreal is what it was, but that was a realm Kantner was well familiar, since helping form Jefferson Airplane, one of the defining San Francisco groups, whose debut album came out 50 years ago this year, and which he retooled into in Jefferson Starship and his own various solo projects.

`We’re one of the few groups left in rock ‘n’ roll that are still alive,” he said when the Jefferson Airplane was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996, the same year David Bowie was. He played three Airplane songs with Jack Casady, Jorma Kaukonen, Spencer Dryden and Marty Balin, but Grace Slick was absent with an inflamed leg. The band gets a Lifetime Achievement Grammy this year.

That version of “Volunteers,” at Connecticut’s Newport Blues Cafe, right on Route 44, was ringing in my memory the last time I talked Kantner, in 2000, when he had a version of Jefferson Starship touring. In the conversation, he denied that the song “Volunteers” even urged political overthrow.

“We were not so much doing political agitating as we were basically news reporters, reporting what was going on,” Kantner said. “We’ve never been per se a political band, enticing people into politics, God forbid. That’s a Jonathan Swiftian world I wouldn’t want to be in.”

Further, he added, “God forbid the revolution would have succeeded. We’d have had Jerry Garcia in charge of the sewer department. And then what?

“‘Take notice of what’s going on, and do something about it’ is what we were saying” on songs like “Volunteers,” Kantner said. “There is a revolution, an ongoing revolution going on every day. Look back at the fall of the Berlin Wall, which happened so fast.”

Plus, he added, “Look at the music business today.”

The hippie vibes of Jefferson Starship stood apart from the pop music of that time, but Kantner said, “We have always stood apart of the music business.”

Indeed, the band flourished in San Francisco, because it has been a haven for outcasts “and crazy people since before the Gold Rush,” Kantner said. “If I was born in any other city, I’m sure I’d have been executed by now.”

“We’re not icons,” Kantner said back then. “But we’ve lived. And we’re still alive. And we’re playing better than we ever have.”

Kantner helped evolve Jefferson Airplane into Jefferson Starship in 1974. But when he quit the increasingly bland Jefferson Starship in 1984, he also took the Jefferson part of the name, the last remaining vestige of the influential Haight-Ashbury band of the late ’60s.

The remaining Starship, which managed to have a few hits with vocalist Mickey Thomas at the helm but “they fell apart,” Kantner said, sounding a bit self-satisfied when I spoke to him a couple of years earlier. “Which I told them they would do, even with the No. 1 hits. But they didn’t believe me.

“If they had not been named Starship, they probably could have been a credible band on their own,” he says. “But they wanted to keep the name to bank on the old audience — who didn’t get what they wanted when they came to the shows.”

He had stolen back the name Jefferson Airplane when he embarked on a “Blows Against the Empire” he was on — 22 years after that album’s release.

“It needed doing, too,” Kantner told me at the time. “There’s an adolescent thrill in re-hijacking the Starship.”

Kantner was hoping the old Airplane audience will be better served by what he was calling Jefferson Starship: the New Generation, which boasted bassist Jack Casady and Papa John Creach as well as a handful of younger ringers.

“We’re like an experimental aircraft. We’ll take it up and see how it flies,” he said. “It usually works better with a new band by going out and playing live first — that’s at the heart of most music. If you can move somebody live, then you have something.”

That’s what happened with the Airplane, which formed in 1965 and played all over San Francisco, before they released their first album the following year.

“We’ve never been a recording band in that sense,” he said, speaking of his various incarnations of Jefferson. “Whatever we do, it usually starts in front of a group of people.”

The last time the Jefferson Airplane toured was in 1989. “We had a good time on stage,” Kantner says. “But a bad time off stage dealing with everybody’s agents and managers.”

“We’re all pretty iconoclastic people,” Kantner said. “That was the strength of the Airplane, we all came in with a different viewpoint.”

Kantner at the time was still writing new songs, that he described briefly. “Some address politics,” he said. “Some address science fiction. Or outlaws. One is about a woman serial killer of Republicans, written in Jonathan Swiftian mode. There’s another song that says, `The sky is full of ships tonight’ — science fiction stuff.”

But at the time he was still enthused about the Next Generation, and returning to aviation metaphors. “It’s blending together really nicely,” he said. “I could take this for as long as it flies.”