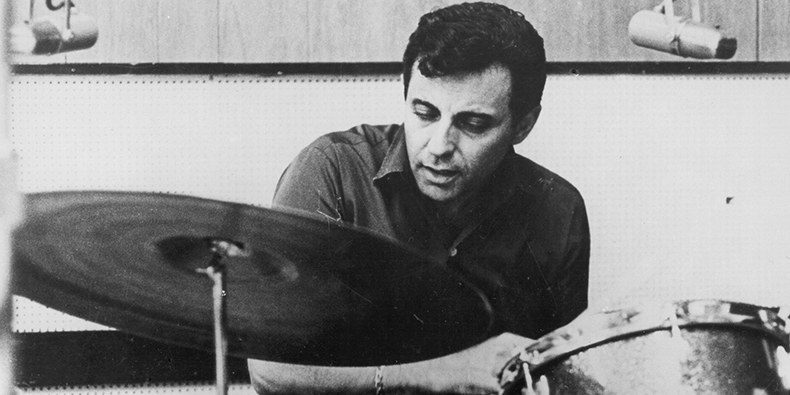

One of rock’s greatest timekeepers was stilled, as Hal Blaine died in Los Angeles Monday at age 90.

One of rock’s greatest timekeepers was stilled, as Hal Blaine died in Los Angeles Monday at age 90.

A player on more than 350 Top 40 hits and 40 No. 1 records, Blaine was something of a hometown hero in Hartford, where I was working when I interviewed him in 2000, as he was about to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the first group of studio sidemen so honored.

It was fitting that the ceremony was being held at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, he told me, since “one of my first jobs was at the Waldorf, playing that room with Count Basie and Joe Williams.”

Blaine, then 71, thought it was odd he was being inducted as a “sideman,” though. “I don’t know why they didn’t call it ‘session men’ instead of sidemen,” he said. “The funny part of it is that just about all of us were leaders.”

That was certainly the case with Blaine, a trained musician who composed and wrote down his own drum parts to a head-spinning number of ’60s hits. It’s still impossible to turn on an oldies station anywhere and not hear Blaine’s work more than a dozen times a day. He played on nearly all of the Beach Boys’ hits, from “Fun, Fun, Fun” and “California Girls” to the more groundbreaking “Pet Sounds” and “Smile” sessions.

Blaine made his name as part of Phil Spector’s studio band, known as the Wrecking Crew, where his thump announced to the world the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby.” He played on Elvis Presley’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love With You” and “Return to Sender,” Roy Orbison’s “It’s Over,” Dean Martin’s ”Everybody Loves Somebody,” Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night” and most of the Simon and Garfunkel hits, from “Homeward Bound” to “Mrs. Robinson.” It’s probably easier to list the performers of that era with whom Blaine didn’t worked.

“During the ’60s, Hal was undoubtedly the busiest, most recorded and most successful studio drummer on the West Coast,” E Street Band drummer Max Weinberg wrote in his book “The Big Beat.”

“If you wanted to work in L.A. at that time,” drummer Jim Keltner has been quoted as saying, “you had to sound like Hal Blaine.”

Blaine’s first taste of drums came while growing up in Hartford, when he started watching the fife and drum corps at the Catholic school across from his Hebrew school. “I was about 9,” Blaine said. “One of the priests noticed I was watching, and before long I was playing with these kids. That was my beginning.”

He was born Harold Simon Belsky in Holyoke, Mass., in 1929, but Hartford provided his “first taste of show business,” he said.

“My dad was working for Connecticut Leather down on State Street. He would take me to work on Saturday morning,” he said, “and I’d be the first guy in line with a quarter at the theater.”

At places like the old State Theatre in Hartford, “I saw every major band, every singer, every vaudeville act, every dance act. I’d sit there all day long.

“My great influences were big bands. I idolized people like Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Frank Sinatra — never realizing I’d get to work with all these people later on in years.”

Blaine’s family moved to California before he graduated from Weaver High School. After a stint in the Army, he used the G.I. Bill to study drums in Chicago, where he also played strip clubs.

Back in California, he played in “funny hat bands” that popped up in nightclubs, backing such little-known comedians of that day as Buddy Hackett and Don Rickles. (Blaine returned to those rim-shot days with his 1996 recording, “Buh-Doom,” produced by David Grisman.)

His first big break came when he agreed to drum for Tommy Sands, the pop vocalist of the late ’50s with hits like “Teen-Age Crush.”

“Those were the first days of kids trying to pull our clothes off,” Blaine said. “It was great training, and wonderful money.”

And he got to know producers at Capitol Records, who kept him in mind when it came time to record rock ‘n’ roll, which to Blaine was “blues with a beat.”

He joined with a number of other studio whizzes at the time, from Leon Russell to Glen Campbell and Sonny Bono (“basically a go-fer at the time”) to form the Wrecking Crew, which backed Phil Spector’s unique Wall of Sound recordings.

“The older people said, ‘These kids are going to wreck the business,”‘ Blaine said. “So we became the Wrecking Crew.”

“Spector recorded like nobody else in the business,” Blaine said. Instead of a spare rhythm section, the eccentric producer “used three or four basses at the same time, always four pianos, as many as seven guitars — that’s why it was called the Wall of Sound.”

“It was an incredible time,” Blaine said. “Any time there was a Spector session, everybody wanted to come down and see what magic fairy dust he was sprinkling on the records.”

One of them was Brian Wilson, a Spector devotee who gave Blaine lots of freedom in drumming on scores of Beach Boys tracks. “Brian always told me to just do my thing, ” Blaine said.

“He was like the drum beat, the tempo man,” Brian Wilson said in notes to the “Pet Sounds” boxed set. “As a matter of fact, he came up with more of the tempos than I did.”

Even when Wilson asked the band to don fire hats during one passage of the experimental, ultimately aborted “Smile,” Blaine thought nothing of it. “It was just a big party,” he said. “It was one of Brian’s ideas to just do anything.”

Few knew it at the time, but even in established bands with star drummers, Blaine was the only one whom producers trusted to actually play on the tracks in pop groups ranging from the Monkees to the Mamas and the Papas and Grass Roots.

“We were the original Milli Vanillis,” Blaine said. “I replaced almost 200 drummers in groups and bands when they used me in the studio.”

So strong was his hold on recording sessions that he played drums on eight Grammy-winning records of the year, seven consecutively. The run began with Herb Alpert’s “A Taste of Honey” (where the bass drum break in the middle of the song was Blaine’s idea) and continuing with Sinatra’s comeback breakthrough, “Strangers in the Night.”

Blaine’s association with Elvis Presley came in part because the King’s manager, Col. Tom Parker, had also been Sands’ manager. Blaine ended up heard on Elvis’ recordings and seen in his films such as “Girls, Girls, Girls” and on his standout 1968 comeback TV special.

Sands was also a connection to Nancy Sinatra, who was the singer’s wife at the time. So Blaine played on her hits as well as the comeback Capitol sessions for her more famous dad.

“These producers wouldn’t do a session if I wasn’t there,” Blaine said. “It’s embarrassing to say that. But that’s the way it was.”

Although he recorded some of his own albums of instrumentals, such as 1966’s “Drums! Drums! A Go-Go,” Blaine said, “I’ve never been a soloist. I’ve always been an accompanist.”

It was something of a strain in 2000 for Blaine to come up with his own favorite tracks. Eventually he mentioned Richard Harris’ “MacArthur Park,” Barbra Streisand’s “Stoney End” and the pair of Fifth Dimension Grammy winners.

“I just heard ‘Love Will Keep Us Together’ the other day. That was my last Record-of-the-Year winner with Captain and Tennille,” he told me. “I’m absolutely amazed at how good that record still sounds.

The common thread among all the songs was that they all had a good feel.

“I will say, when we made records in those days, practically every record we made had to feel good. Because people were still dancing in those days, they all had this built-in dance beat. But if it felt good, we knew we had a good record.”

Among the hits on which Hal Blaine drummed:

- “Be My Baby,” The Ronettes

- “He’s a Rebel,” The Crystals

- “Good Vibrations,” The Beach Boys

- “California Dreamin,”‘ The Mamas and the Papas

- “Mr. Tambourine Man,” The Byrds

- “Windy,” The Association

- “Let’s Dance,” Chris Montez

- “Surf City,” Jan & Dean

- “Secret Agent Man,” Johnny Rivers

- “The Beat Goes On,” Sonny & Cher

- “Stone Soul Picnic,” The Fifth Dimension

- “If I Can Dream,” Elvis Presley

- “The Boxer,” Simon & Garfunkel

- “Last Train to Clarkesville,” the Monkees

- “Another Saturday Night,” Sam Cooke

- “Good Thing,” Paul Revere and the Raiders

- “Dead Man’s Curve,” Jan & Dean

- “I’d Like To Get To Know You,” Spanky & Our Gang

- “Eve of Destruction,” Barry McGuire

- “Stand By Me,” John Lennon

- “Katy Lied,” Steely Dan

- “Close to You,” the Carpenters

- “Rocky Mountain High,” John Denver

- “I Think I Love You,” The Partridge Family

- “Mother and Child Reunion,” Paul Simon