For the annual Hobart Street Porch Fest this weekend in D.C., I did some research on the guy for whom the block was named nearly 100 years ago and found out a lot about one of the more obscure names in American history.

For the annual Hobart Street Porch Fest this weekend in D.C., I did some research on the guy for whom the block was named nearly 100 years ago and found out a lot about one of the more obscure names in American history.

Despite the distinctly Democratic slant of our famous Hobart Street Pledge, the namesake of our street was actually a Republican.

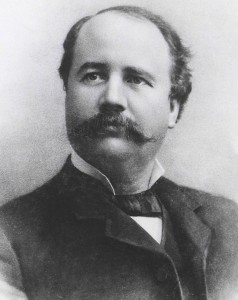

Garret Augustus Hobart (1844-1899), whose nickname was Gus, never lived long enough to see the 20th Century or Hobart Street, for that matter. But the New Jersey politician did become the 24th Vice President of the United States, serving in the administration of William McKinley.

It was rare to have a vice presidential candidate who had not held an office higher than state legislature. Yet that was the case of the Long Branch, N.J. native who rose to speaker in the state assembly as well as president of the state senate president – and was the first to head both houses in New Jersey.

A well-liked man in his state, he was also about as well-rounded as the current New Jersey governor. And at the Republican National Convention of 1896, it was Hobart who emerged from a list of possible running mates for Ohio Gov. William McKinley, who was elected the party’s nominee.

McKinley would have preferred his chief rival for the top of the ticket, U.S. House Speaker Thomas B. Reed, but Reed didn’t want to be anything but top spot. Hobart was chosen because he could help guarantee New Jersey in the Republican’s win column.

Yet Hobart wasn’t very excited about being tapped for the V.P. slot. As he wrote his wife back in Paterson, “It looks to me I will be nominated for Vice-President whether I want it or not, and as I get nearer to the point where I may, I am dismayed at the thought.”

Aside from the honor, he said, “when I realize all that it means in work, worry, and loss of home and bliss, I am overcome, so overcome I am simply miserable.”

Still, McKinley and Hobart made a good team. Their campaign style, I was delighted to find, was called “Front Porch Campaigning,” which had been used in previous successful campaigns by James A. Garfield in 1880 and Benjamin Harrison in 1888. It meant rather than traveling all around to give speeches, as did McKinley’s Democratic opposition, William Jennings Bryan, the two would hold court on their own formidable front lawns, as delegations from various states would travel to see them.

Their own 19th Century version of Porch Fest worked. The McKinley-Hobart team won by a half a million votes, carrying 23 of the 45 states at the time, including Hobart’s New Jersey.

As miserable as he seemed about being nominated, Hobart did a very good job as vice president by all accounts, raising the job to a new importance it didn’t have previously.

Hobart visited the White House more than any previous vice president, presided over the Senate on a full time basis and helped broker some key turns in the McKinley administration, from the five month war and subsequent peace treaty with Spain (following the sinking of the battleship Maine), to the holding of the Philippines at the end of the war by breaking a Senate tie, to obtaining the resignation of the secretary of war, Gen. Russell Alger.

Indeed, he held so much influence on the chief executive that Hobart was often called “Assistant President.”

No Vice President lived as close to the White House as Hobart, who moved into the Benjamin Ogle Tayloe House at 21 Madison Place NW, from 1897 until 1899.

At the “Cream White House,” as it was named (because of its shade of white), the distinctive 1828 Federal style house, which still stands, was site of a number of important meetings, from Prince Albert of Belgium to the International Boundary Commission that set the lines between Canada and the U.S.

There was actually more social occasions there than at the White House in those years, since McKinley’s wife was an invalid. The President quite often attended the dinners and afternoon smokers where he could meet informally with party leaders who also gathered there.

Arthur Wallace Dunn, a newspaper correspondent at the time, who covered presidents from Benjamin Harrison to Warren Harding, wrote that “for the first time in my recollection, and the last for that matter, the Vice President was recognized as somebody, as a part of the Administration, and as a part of the body over which he presided.”

Historians placed Hobart as one of the most powerful Vice Presidents in U.S. History.

And more than that, he was a nice guy. As Hobart biographer (and his pastor) David Magie noted in his 1910 book:

“If his career lacks the exciting interest of the fierce purpose of reckless ambition and of bitter conflicts with rivals and conquest over foes, it always possesses the pleasing attraction of good nature and cheerfulness, winning the kindly feelings of an ever-widening circle of friends…”

So why isn’t Gus Hobart remembered better, even by people on his namesake street? (There are also towns named after him in Oklahoma and Washington State.)

He had a heart ailment, first revealed in 1898 that got steadily worse a year later and he died in late November 1899, at the age of 55. He was the sixth U.S. Vice President to die in office.

Obscuring Hobart in history is the replacement Vice Presidential candidate that McKinley chose for his running mate in 1900, who would usher in the 20th century in his spirit, spend a lot of time hiking Rock Creek Park and who took over the Presidency following the assassination of McKinley in 1901 – Theodore Roosevelt.