Other than Elvis, the number of rock ’n’ roll pioneers that have been still among us all these years is pretty impressive, with Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and Fats Domino still drawing breath.

Other than Elvis, the number of rock ’n’ roll pioneers that have been still among us all these years is pretty impressive, with Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and Fats Domino still drawing breath.

That ended Saturday for the man to whom rock ’n’ roll is closest linked when Chuck Berry, died at 90.

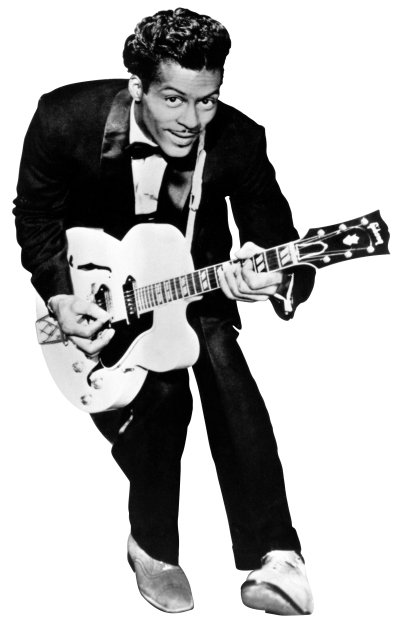

The flamboyant guitarist, lyrics and showman never claimed to invent rock ’n’ roll.

When John Lennon declared “If you had to give rock ’n’ roll another name, you might call it Chuck Berry,” he was reading it off a cue card on “The Mike Douglas Show” the week he was co-hosting in 1972.

Instead, Berry always credited big band leaders, particularly Louis Jordan, whose songs were filled with the same kind of sly wordplay, and whose guitarist Carl D. Hogan originated the riff was used to introduce “Johnny B. Goode.”

Though I saw his show a couple of times, I never spoke to Berry. I did get to interview the influential pianist in his trio Johnnie Johnson in 1991. It was Johnson who hired young Berry to play guitar in his East St. Louis, Ill., band on New Year’s Eve 1952 to replace an ailing saxophonist.

“He was playing hillbilly type of music, country-western,” Johnson recalled. “I think that’s what won him over to the teenagers and whatnot. And as you know, they always say he’s the father of rock ‘n’ roll. And this is the type of music we were playing — before it was called rock ‘n’ roll.”

Johnson appreciated his approach, and also his showmanship.

They became in synch in echoing each other’s melodic patterns — so much so that the famous Chuck Berry chords can be traced to Johnson’s ivories.

That was the guitarist’s grail that Keith Richards discovers in the Berry documentary “Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll.”

Instead of playing in A, E or G, Berry was playing “in piano keys, jazz keys, Johnnie Johnson’s keys,” Richards says in the movie, chronicling the 60th anniversary concert he helped organize. “Chuck adapted those riffs to his guitar. Then he put on those great lyrics behind them.”

Besides the enduring rock riffs, and the duck-walk showmanship, Berry stood out for his splendid lyric wordplay.

He gleefully made up words that suited him — Does he say “As I was motorating over the hill” in “Maybelline”? Is that a “Coolerator crammed with TV dinners and ginger ale” in “You Never Can Tell”? (Well, actually that was the brand of a fridge in the midcentury, just as Roebucks was in the same song).

In “Memphis,” he gave us the splendid line, “Last time I saw Marie, she’s waving me good bye / with hurry home drops on her cheek that trickled from her eye.”

In “Thirty Days,” he warned, “If you don’t give me compensation, I’m going take you to the United Nations,” three years before Eddie Cochran cited the same organization in “Summertime Blues.”

The complicated wordplay on “You Can’t Catch Me” was so indelible, John Lennon lifted “Here come a flat-top, he was movin’ up with me” to kick off a Beatles single 13 years later, “Come Together.”

Musically, Johnson told me, “we exchanged ideas a whole lot on some of his songs.” But, he added, ”All the lyrics were his doing.”

If it wasn’t American enough to hear him sing of cars racing, how about the litany of towns he’d sing in “Promised Land” or “Living in the U.S.A.”?

In the former, Norfolk, Va., Raleigh, Charlotte, Rock Hill (S.C.), Atlanta, Birmingham, New Orleans, Houston, Albuquerque, Los Angeles; in the latter, New York, Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago Chattanooga, Baton Rouge and Ol’ St. Lou — just to mention the second verse.

His first spate of hits started to wane about the time British kids were picking up on his sound in their own bands. His chords became the basis of the Rolling Stones, whose first single was a cover of his “Come On.” A wider audience caught the spirit and drive when the Beatles sang his “Roll Over Beethoven,” the first song played on their first U.S. concert in Washington, D.C. in 1964 (“You know, my temperature’s risin’ and the jukebox blows a fuse / My heart’s beatin’ rhythm and my soul keeps on singin’ the blues”).

Every guitar player worth his salt learned (and for a moment imagined himself as) “Johnny B. Goode,” playing a guitar like a ring in a bell.

Berry’s thematic concerns would echo years later in Bruce Springsteen as well, from “Downbound Train” (Berry’s 1955 B-side to “You Can’t Catch Me” became title of a track on “Born in the U.S.A.”) to “Promised Land.” And Springsteen would take the mythos of “Johnny B. Goode” and “Bye Bye Johnny” for his own “I’m On Fire” B-side, “Johnny Bye Bye” in 1985.

If Berry’s power in the charts waned in the 60s, the Stones kept doing covers of things like “Little Queenie,” “Around and Around” and “Carol” keeping his songs alive. A whole new generation may have picked up on the teenage abandon he conjured when “You Never Can Tell” was picked for the memorable dance in “Pulp Fiction” in 1994.

It’s one of the sad things about the Berry story that his last hit, which would also be his biggest No. 1, was also one of the dumbest songs on the charts in 1972, a live sing-along to Dave Bartholomew’s blue novelty “My Ding-A-Ling.”

The last time I saw Berry play live was for the big concert that was opening the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland in 1995.

The big show at Municipal Stadium was light on the kind of huge stars that lit up their induction dinners (no Stones; no Beatles), but there was Jerry Lee Lewis, the Kinks, Dylan, and opening and closing the show, Berry backed by Springsteen and the E Street Band.

Even an acolyte like Keith Richards couldn’t help show frustration in backing Berry for the big 60th birthday Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll concert. Springsteen too, earlier in his days, had been one of those hapless local backing bands hired to try and follow Berry, who’d famously mess with his backing bands.

As shaky as “Johnny B. Goode” was to open the show, the closing “Rock and Roll Music” was an absolute mess, starting and stopping and not ever settling into one key. It was as if he was suggesting, “This is my ball, and I can take it home anytime I like.”

Berry kept performing through the last couple of decades, usually closer to his St. Louis home.

Even as he limited his appearances, his sound remained everywhere, as the basis for rock ’n’ roll of every stripe. Without it, the bands I happened to see Thursday — Dan Baird & Homemade Sin and Eric Ambel — wouldn’t have that sound, or be there at all.

Even Stephin Merritt, amid the chamber folk hymns of the Magnetic Fields new album Saturday night, paused to dedicate a song “To Chuck!” (called “Rock ’n’ Roll Will Ruin Your Life”).

When the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened last fall in D.C., its vast fourth floor Musical Crossroads was fronted with not only Berry’s guitar, but his shiny 1973 red Cadillac Eldorado, the very one driven on stage during the “Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll” concert in 1986.

“It’s more than just a shiny object that’s standing in the center of the museum,” Musical Crossroads curator Dwandalyn Reece told me.

“It’s also a symbolic element of Chuck Berry’s own personal story and career, tied to his relationship, growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, and not being allowed to go to the Fox Theatre as a child, because of his race. And then you have this moment where he’s driving a car across the stage at this same theater 40 years later.

“Everything represented by that,” she sad, “The freedom and liberation and sense of achievement of an African-American man who is one of the architects of America’s greatest exports, rock ’n’ roll, and what that says about music from that standpoint; where music functions as a tool of liberation and protest and individuality in American culture and African-American culture.”

It’s the kind of upward struggle he sang of in everything from “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” to “Promised Land.”

And Berry’s music will not only continue to be heard for many years to come — its durability may also be measured in terms of light years, as “Johnny B. Goode” was chosen as the only rock ’n’ roll song to be sent out into space to tell other beings in realms we can’t imagine, something special about our planet and its people.

And on Earth, he’ll be continue to be heard as long as there’s a guitar player who plays like a ring in a bell.