One day before his 92nd birthday, jazz great Dave Brubeck died at Norwalk Hospital in Connecticut on Wednesday.

One day before his 92nd birthday, jazz great Dave Brubeck died at Norwalk Hospital in Connecticut on Wednesday.

The pianist and composer was one of the first huge stars of the genre, giving a face and personality to the movement, much to his own embarrassment.

Brubeck’s genius came in combining elements of classical and jazz music and using unusual and often challenging time signatures. His biggest hit album, “Time Out,” is dedicated to that proposition, and its biggest hit, “Take Five,” took its name from its unusual 5/4 time signature.

Likewise, “Unsquare Dance” is in 6/4 time; “Blue Rondo a la Turk,” is in 9/8.

Brubeck was able to accomplish this through a remarkable group that included percussionist Joe Morello, bassist Eugene Wright and the distinctively sweet saxophone sound of Paul Desmond, credited with doing the melody and writing for “Take Five,” the anthem that became his trademark and one of the best known jazz tunes.

Brubeck was born in Northern California to a rancher and a piano teacher who was bent on a more classical approach to music. Her emphasis on Chopin would come to serve Brubeck well late in his career, when, as a jazz ambassador to the world, he was touched by the composer’s music while visiting Poland.

The other classical influence came from studying with French composer Darius Milhaud while at Mills College in Oakland, Calif. Milhaud was one of the first composers to freely include jazz in his compositions, and he encouraged Brubeck to do what he did best: pure jazz. Brubeck met some of the musicians with whom he’d later make history while playing in the A.S. Army Band, which took him out of Patton’s force during World War II.

It was the piano work of Art Tatum that inspired Brubeck most as a youngster, and he convinced his mother when one of Tatum’s songs came on the radio.

In “Dave Brubeck: In His Own Sweet Way,” a documentary that jazz fan and filmmaker Clint Eastwood released in time for his 90th birthday two years ago, Brubeck recalled, “She said to me, ‘David, now I understand why you want to play jazz so much.”

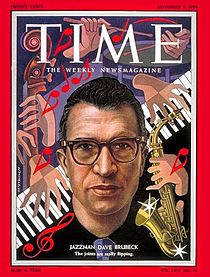

What Brubeck’s trio, and later quartet, created in early nightclubs like the Black Hawk in San Francisco they also took to college campuses in shows often booked by his wife, Iola. Those shows helped create a new generation of jazz fans and a groundswell for the music. When Brubeck was featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1954, he was somewhat embarrassed that the publicity didn’t go instead to one of the influential black musicians he followed.

Still, Brubeck’s West Coast “cool” seemed to contrast with the hot jazz of the East Coast for some, though Brubeck himself denied such categorizations.

Cool or hot, Brubeck represented something else in jazz — a studious, serious musician and family-oriented man; he moved to Connecticut in 1960 to raise his family. He was a player who avoided the clichés of drugs and dissipation often associated with jazz musicians.

After breaking up his quartet in the 1970s, Brubeck not only grew out his hair but expanded his ambitions, composing orchestral and choral works. Eventually he brought back the quartet sound as well, in a group that in recent years included sax player Bobby Militello, bassist Michael Moore and drummer Randy Jones.

In 2009, Brubeck delighted to the sight of his four grown sons, Darius, Dan, Chris and Matthew, playing his music onstage in Washington when Brubeck became a Kennedy Center Honoree.

Brubeck continued to perform and compose, playing more than 50 concerts in 2010, including the Litchfield Jazz Festival in nearby Kent, Conn., and joining the Wynton Marsalis Quintet at the Newport Jazz Festival before he began to encounter the heart problems that led eventually to his death.

The reason he kept working so late in life was addressed in Eastwood’s film by jazz fan Bill Cosby, who said, “When Dave comes out and that applause goes up, at this time in his life, it is not only the dexterity, the thought, the improvisation; it is also the ‘thank you.’ Because that music is doing what he loves to do and what he wants to do.”

Here’s a performance of his best known song from a 1966 show in Germany: