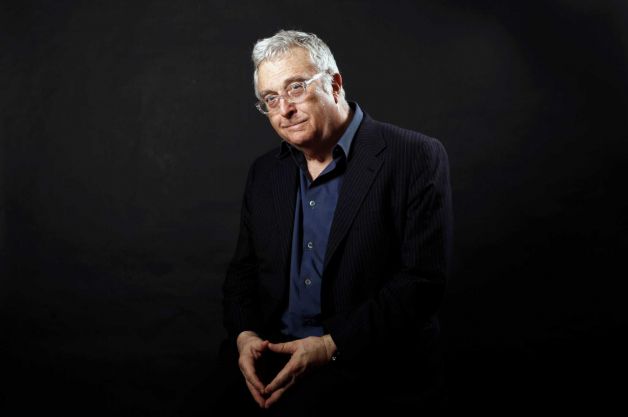

At the Library of Congress Randy Newman concert Saturday, it was kids beware.

At the Library of Congress Randy Newman concert Saturday, it was kids beware.

If they came to hear one of his many songs from Pixar animation — certainly his most successful tunes of the last two decades — they could hear only one.

And even then, the inevitable “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” came with it a irascible, borderline saucy story about the film from which it came “Toy Story,” and some cranky reminiscence about seeing the movie the first time (he didn’t notice that it was animated or a comedy).

Mostly, Newman at 69 played the cranky uncle, decrying the history of the world and its current greatest woes, but playing it beautifully on piano, using a mix of updated ragtime and New Orleans barrelhouse, mixed with a kind of timeless Americana of Stephen Foster. In a kind of lighting bonus on the stark paneled stage, reflections of the Steinway hammers as they pounded strings reflected on the ceiling, a kind of unintended musical rainbow Newman wool have likely growled about as well.

The carefully selected set list painted a character who was a hateful, hopeless misanthrope — a character whose first person rantings might make the uninitiated think Newman the worst person in the world. Most seem to understand the funny songs were pointed satire of the human condition.

“It’s Money That I Love,” he began (“Nothing like a good spiritual to start things off”), turning to “Birmingham,” a love song to a city of hate. He dispatched his biggest chart hit, “Short People,” early on, spitting its stereotypes afresh amid its forgotten chorus of feigned brotherhood. He continued his dismissal of the poor in “My Life is Good.”

Later came darker observations, the woeful history of “The Great Nations of Europe,” the celestial dismissal of “God’s Song.”

All this dark humor and pessimism only makes the plaintive ballads that much more stark and beautiful, from “Marie” and “I Mss You.” Not enough is said about Newman’s mastery of melody, whose lilts convey as much as his well chosen words. It makes “Louisiana 1927,” which name checks the president for whom this hall was named, sounds like a beautiful lament of natural disaster, but ultimately serves as another dismissal of the powerful of the plight of the poor.

The D.C. crowd appreciated that he brought back “Political Science” late in the show that was postponed a month due to the government shutdown. But it was largely his latest and songs that were more effective, despite what he says about his own extended stay in show business, “I’m Dead and I Don’t Know It.”

Just about everybody stayed for the the Q&A that followed the performance, a chance for him to ruminate on his favorite contemporary writers (Kanye West and Eminem among them, though he said writing rap lyrics was like playing tennis without a net — easier than it was for songs). He also spoke at length about the fraud of conductor’s flourishes.

Best is when he turned back to the piano for examples — a beautiful instrumental that was a homage to his uncle who wrote scores for John Ford (“Outdoors but Not the Red River Valley”) and, by memory “A Few Words in Defense of Our Country” (which he said the Library of Congress had not censored from his set; he just figured it was more appropriate during the Bush administration).

And instead of a final question, a final request: The exquisite “Feels Like Home.”

In a warm performance in the nation’s capital from the Gershwin Fund, he sure seemed like it.