“Tommy,” the groundbreaking 1969 set by the Who that it dubbed a rock opera, finds a new dimension in the Open Circle Theatre production in Silver Spring.

“Tommy,” the groundbreaking 1969 set by the Who that it dubbed a rock opera, finds a new dimension in the Open Circle Theatre production in Silver Spring.

While there’s still much puzzling in the plot of the piece by Pete Townshend, adapted and somewhat watered-down for Broadway in the mid-90s as “The Who’s Tommy,” the exuberant production plays on the now outdated anthems of “that deaf, dumb and blind kid” by doubling all of the main characters with American Sign Language interpreters.

The pairings fit perfectly in a work that is already dominated by a mirror that eventually shatters – as this production does to barriers.

Providing opportunities for theater artists with and without disabilities has been the goal of Open Circle Theatre from its outset, returning after a five year hiatus with this production, And the star of this “Tommy” is a real one – the Gallaudet University educated Russell Harvard, whose work includes everything from “There Will Be Blood” to the Deaf West Theater Broadway revival of “Spring Awakening” to his role as the menacing Mr. Wrench in season one of FX’s “Fargo.”

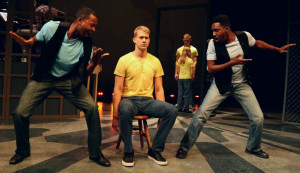

While most of the large cast in the production are shadowed by similarly dressed actors doing ASL, Harvard is the memorable star in the forefront, with Will Hayes singing the keening anthems like “See Me, Feel Me” behind him.

What’s more, this “Tommy” marks the welcome comeback Monica Lijewski, a favorite local Equity actress in a variety of musicals, who fell eight feet into an empty orchestra pit while rehearsing her role as Mother Abbess in “The Sound of Music” at Onley Theatre Center five years ago.

Paralyzed from the chest down, she sings and zips around the stage in a wheelchair as a member of the ensemble.

Managing the sheer traffic of humanity on stage is one of the chief achievements of OCT artistic director Suzanne Richard’s direction, who weaves a veritable team of Tommys – two child Tommys, one singing, one ASL and one more – amid a whole town-full of intermingling characters (and signers).

This on a stage that’s already dominated by a house band of a half dozen on a raised platform who have the unenviable task of replicating the dynamic music of one of rock’s greatest bands that had music’s most explosive drummer in Keith Moon behind Townshend’s slashing guitar and John Entwistle’s inventive bass.

They have to do this while being quiet enough so the vocals, amplified by headphone microphones, can still be heard. It was surprising, too, how much guitars took the backseat to keyboards in the musical direction of Jake Null, a Helen Hayes winner for his work on “Avenue Q.” It’s like hearing “Tommy” as performed by Elton John.

The music grandeur almost makes up for a plot that still doesn’t quite add up as it reaches its half-century mark. Briefly, it’s this: A young boy is traumatized by seeing his father, returning from a war where he was presumed dead, kill his mother’s new lover. As a result, he can’t see, hear or respond. As such he is subject to all manner of abuse from cousins, uncles and questionable doctors.

Somehow he becomes a pinball champion despite it all. And when his mother (a vocally dynamic Autumn Seavey Hicks) smashes a mirror he’s been constantly staring into, he’s suddenly “cured.” This makes him a superstar, then a religious figure who is ultimately disillusioning to his followers, then someone who ultimately craves a connection through the senses: “See me, feel me, touch me, heal me.”

What may be unexplained in a linear way may be nonetheless felt through the music’s sweep, though the final stirring words of the opera are more a series of praises for Townshend’s religious hero at the time, Meher Baba (“Listening to you, I get the music / Gazing at you, I get the heat”).

Still, the Broadway version with Des McAnuff muddled things more, with a minor character in a jaunty side-story, Sally Simpson (Monica Janiga) suddenly becoming a Tommy love interest, and a wholly unnecessary song with a completely different tone inserted in the second act meant to explain the parents’ relationship (why start now?), “I Believe My Own Eyes.”

Yes, “Pinball Wizard” was the hit from the album, but that doesn’t mean they have to play it three times to keep interest.

And there’s so much abuse in the original, from “Cousin Kevin” (played by Carl Williams with Aarron Loggins on ASL) to the “Fiddle About” perversions of Uncle Ernie (Mikey Cafarelli) that the young Tommys, played by Kira Mitchiner and Chloe Mitchner are subbed out by grownup Tommy, Harvard, to keep it a tad more bearable to see. (Likewise the line “gonna rape you” in “We’re Not Gonna Take It” is cut once and altered to “maybe rape you” the single time its uttered).

Time was always a puzzle in the work, but here it’s spinning out of control, with the baby still born in “1921” but the war involving Malcolm Lee’s Captain Walker a contemporary one, with the World Trade Center burning in Arnulfo Moreno’s projections and the captain a possible victim of a Taliban beheading. Everybody seems to have a cell phone.

Still, Jeremy Stubbs’ scenic design is something of a marvel, with a big dark jagged shape cutting into the space and the shattered shards emanating from the mirror reflected in the floor covering.

It helps retain focus on the duality in the production that not only enhances the classic music, but the mission statement of the group making its welcome return.

“The Who’s Tommy” by Open Circle Theatre continues through Nov. 20 at Silver Spring Black Box Theatre, 8641 Colesfille Rd., Silver Spring, Md.