As an artist, Patti Smith is nothing if not multi-disciplanary. She began as a poet. She hung around with Robert Mapplethorpe. I read her as a rock critic in magazines like Circus before her first recordings slashed a hole into the complacency of rock, circa 1976. She was influential and inspiring in her role as thoughtful, enigmatic rock frontwoman, and seemingly disappeared for years into domestic life before returning in part to find a way to express losses in her own life.

As an artist, Patti Smith is nothing if not multi-disciplanary. She began as a poet. She hung around with Robert Mapplethorpe. I read her as a rock critic in magazines like Circus before her first recordings slashed a hole into the complacency of rock, circa 1976. She was influential and inspiring in her role as thoughtful, enigmatic rock frontwoman, and seemingly disappeared for years into domestic life before returning in part to find a way to express losses in her own life.

It took forever for her to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but almost no time at all to win a National Book Award for her reminiscence of her Chelsea days with Mapplethorpe, “Just Kids.” Having conquered multiple fields, it’s time for her to break new barriers, this time with her first museum exhibit of her photography.

Smith has been one to hang an old Polaroid around her neck as she traveled the world and knelt at the literal graves of her heroes. It was something she kept close as she was interviewed in the 2008 film “Dream of Life” and now we see some of what she produced.

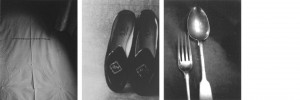

“Patti Smith: Cameras Solo,” at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford through Feb. 19, includes over 70 images, all of them the original, palm-sized Polaroid print, just as they magically developed before her when she took them. They are not a good look into the rock world, but more a curated tour of the poetic one, with gravestones, personal items and bed linens of revered poets and heroes, from Rimbaud to Blake, Virginia Woolf to Robert Botano, each capured in the intimacy of the frame, in a gauzy sands of time effect caused by the Polaroid’s limited field of focus and the black and white film.

Her own eye is most important, as she frames each shot as she sees it – there’s no opportunity for darkroom fiddling with image, size, cropping or contrast with the Land camera. She shoots an image the moment it seemingly impresses her as having the weight of classicism about it, whether it’s Rimbaud’s spoon, Whitman’s tomb or her father’s prized china teacup. A viewer is invited to see what she brought to totemic objects as she presents not just the photo “Robert’s Slippers, 2002” but also Mapplethorpe’s actual monogrammed pair.

Her own eye is most important, as she frames each shot as she sees it – there’s no opportunity for darkroom fiddling with image, size, cropping or contrast with the Land camera. She shoots an image the moment it seemingly impresses her as having the weight of classicism about it, whether it’s Rimbaud’s spoon, Whitman’s tomb or her father’s prized china teacup. A viewer is invited to see what she brought to totemic objects as she presents not just the photo “Robert’s Slippers, 2002” but also Mapplethorpe’s actual monogrammed pair.

Her mesmerizing spoken voice is absent except for a film she narrates. It too, in black and white and illustrating her words. I have heard, however, that the cell phone tour of the works is an indispensible way to experience the show – as one is intimately close to the works, dictated by their tiny size, you have to step in close, it’s likely multiplied by hearing her voice describe her thoughts on the shot, right in your year).

The gravesites add a solemnity to the show. And there’s something missing – the snap and sizzle of her rock and roll. She played a show to mark the opening, but spent half the time reciting poetry and in reverie for her favorite writer, Rimbaud, whose birthday it was.