Been spending most of the week in the basement, seemingly the best place to listen to “Bob Dylan and the Band: The Basement Tapes Complete.” It’s also where my stereo is, so it’s not that much of a stretch.

Been spending most of the week in the basement, seemingly the best place to listen to “Bob Dylan and the Band: The Basement Tapes Complete.” It’s also where my stereo is, so it’s not that much of a stretch.

To read the liner notes for the six-disc collection, though, you’d think that basements were never used for making music before Bob and the rest of The Band rolled into Woodstock, N.Y. and began jamming.

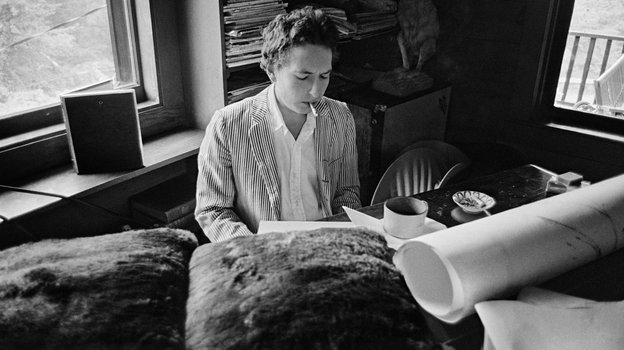

Abruptly exempt from touring and other responsibilities of being a rock star because of a concerning report of a motorcycle accident, Dylan was having fun in upstate New York, hanging around, writing songs and running through them with the group that had accompanied him on his 1966 English tour.

As others had their Summer of Love, he was as far away from crowds as possible in the country, playing covers and the funny new songs he’d dash out in longhand and on typewriter at an astonishing rate.

Ostensibly they were recording so as to make demos of songs that would be offered to other artists and would become hits for them — “Quinn the Eskimo” for Manfred Mann; “Wheel’s on Fire” for Brian Auger; “I Shall Be Released” for Joan Baez.

Naturally the acetates made to pass to artists led to the invention of the bootleg industry when “The Great White Wonder” began appearing in record stores and head shops. Not only did it further curiosity over the M.I.A. artist, it shed a light at what he was up to, blending funny songs (“Please Mrs. Henry,” “Million Dollar Bash”) with some of his most stirring (“I Shall be Released,” “Tears of Rage”).

The dozen or so tracks were plucked from hours of recordings — of covers, shards of other originals, new versions of his old songs — in a manner that makes complete sense with the contemporary Dylan, who is remaking his songs each night on tour while bringing out odd covers (lately from the Sinatra songbook, foreshadowing an album coming out next year).

The mystique of what were called The Basement Tapes led a commercial release, finally, in 1975 that was cleaned up, augmented by bass and drum tracks — and a handful of songs by The Band that were never part of those basement sessions.

The bootlegs kept coming out — multivolume series of every take, though there are some things on the new collection that hadn’t been on any of them supposedly.

Some of these things have leaked out over the years. “I’m Not There” became the title for the movie about Dylan and its soundtrack. Others showed up on earlier vault excavations.

And while Greil Marcus made you think Dylan was tapping directly into the more arcane edges of “The Old, Weird America” and especially the American Folk Music collections of Harry Smith, it’s actually much more varied, with some 50s doo wop, gospel, Johnny Cash country and a number of odd originals, each done a few different ways.

“You’re wasting tape,” Dylan says at one point. But letting the tape roll led eventually to this big release, available in modest two disc package as well as the whole hog box. And the feeling throughout is a group of people having fun knocking through these tunes they were playing solely for their own pleasure.

“There’s a difference playing music for yourself and playing it for a wider audience,” Rhiannon Givens says in the documentary film “Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued” that accompanies yet another Basement project this season, an album called “Lost on the River: The New Basement Tapes .”

Like the “Mermaid Ave.” recordings that had Wilco and Billy Bragg putting music to found Woody Guthrie lyrics, this was an album made by the collaboration of Elvis Costello, Marcus Mumford, Jim James from Morning Jacket, Taylor Goldsmith from Dawes and Givens — working individually but also in a band.

Finding a trove of hand written and typewritten lyrics from that summer in 1967 challenges them to finish the song — a daunting task to say the least.

(And an unnecessary one: Unlike Guthrie, Dylan is alive and well enough to have finished them himself, but apparently showed no interest).

In comments he recorded that are part of the narration of the documentary that airs on Showtime that are in some cases the most interesting part of the film, Dylan claims to have no memory of writing any of these songs.

It was the most prolific songwriting year in his career – with more than 175 songs penned.

Not a single one of them were things Dylan intended to record. He made his demo record that became the Great White Wonder and became the basis of the 1975 Basement Tapes to sell to other artists.

And indeed, the songs the contemporary artists come up sound largely brittle, commercial, with a modern sheen that belies the ramshackle spirit of what we hear performed on the box.

It’s interesting to see the process of collaborative recording today, with Costello and James having recorded songs on their iPhone (the prolific Costello having recorded his in an airplane bathroom; he holds the result to the documentary sound man’s boom mike). But some of the approaches — particularly the cosmic approach of James — seem to be leaving the Dylan lyrics behind.

“Lost in the River” is the thing that attracts a few of the artists; Givens’ stark, gospel-tinged version seems the best of it. But those seeking a taste of Bob Dylan’s basement creativity circa 1967 are advised to go to the unadorned real recordings, scrubbed up as best as possible from what was in Garth Hudson’s archives, rather than the new versions.