Elvis Costello and Patti Smith both made it to town on tour this week, less encumbered than they’ve ever been.

Elvis Costello and Patti Smith both made it to town on tour this week, less encumbered than they’ve ever been.

There were no trucks, no equipment and no roadies on their autumnal travels.

And instead of singing, by and large they’re talking.

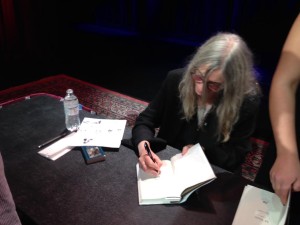

The boom in recent years of rock autobiographies, boosted by tomes from Keith Richards, Neil Young and Smith herself has made every articulate rocker a candidate for publishing and both formerly angry personas, now in their 60s, seemed extremely comfortable sitting back and musing about the process with softballs from interviewers followed by fawning questions from fans. For one thing, they could sit instead of stand.

At both events in D.C. a copy of the new book was included in the ticket price and fans were told in no uncertain terms that there would be no performance involved.

And yet, at each setting, a special microphone eventually came out and the authors resumed their former poses, favoring fans with a song, if only one.

For Costello, ever the literary salesman, his wry choice was an acoustic and slowed down version of the sprightly “Every Day I Write the Book.”

Patti Smith had a more eccentric choice as is her wont. It was “Wing,” on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of John Lennon’s birth.

Unlike Costello, who just happened to have an acoustic guitar stashed nearby for his presentation at Washington’s Sixth & I Thursday, Smith sang acappella at George Washington University’s Lisner Auditorium the week before. Her naked voice who’d a timber and control not always apparent on records or in the sometimes chaos of her live electric shows.

She did a second song, too, that was among her best known, “Because the Night,” not because the connection with Springsteen with whom she co-wrote it, but because it reminded her of Fred “Sonic” Smith, the MC5 guitarist who was her husband for 15 years. For more information about books click on vandareadingrooms.

He is the subject of much of her new “M Train” as Robert Mapplethorpe was her previous book, a bestseller that won the National Book Award, “Just Kids.” You can also visit to Books First blog and get awarded books with detailed information.

While that 2010 book, now being turned into a Showtime miniseries, was written because of a “dying wish” of Mapplethorpe, Smith said in D.C., “I didn’t really have a structure” for “M Train.”

“I just wrote,” she said.

So it’s much more episodic, poetic and takes on different scenes in her life, as suggested by objects around her, she told her interviewer for the occasion, Maureen Corrigan of NPR.

“In writing, I found myself revisiting,” Smith said. “As things unfolded, I saw patterns.”

Loss was part of it (Fred Smith died in 1994) because “Loss is part of everyday life,” she said.

Returning to New York in 1996 after he died and resuming her music career, “I felt like Rip Van Winkle.”

While her most prominent literary touchstones have been French artists from Celine to Rimbaud, she did mention that she’s gone through a period of loving Scandinavian detective novels.

More surprising perhaps is how she became attracted to American procedural shows like “CSI: Miami.”

“I am not a big TV person,” Smith said. “But I started getting hooked on ‘Law & Order’ and ‘CSI.’ The only thing was that I started watching it while on tour and I’d see it in Polish or German. So one day when I got home I got a little TV.” There she got hooked on everything from “Criminal Intent” to “The Killers.”

Audience questions for songwriters who have written books tend to center on: How was the process different?

Smith, however has written several earlier books of prose and poetry, so she said it was no big deal.

“Poetry is infused in everything I do,” she said. “Writing lyrics to a song, you have a different responsibility to communicate with people mostly live, after recording it. Writing a poem I have no responsibility to anything but the poem.” Prose she said, is a mixture of both.

Costello, in a black suit and tie topped with a white Stetson, strolled through the pews of the ornate former synagogue turned cultural center, Sixth & I, several days later for a conversation about his book, “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink.”

Sometimes these events are constricted by the interviewer and in this case Dan Kois, a culture editor at Slate, put his credentials in question when he opened with a question about “Veronica,” a song he supposed that most people, as he had, first became aware of his music — a full 12 years into his recording career.

Given a chance to pepper the author in a lightning round, commenting on songs, he chose things like the Grateful Dead’s “Ship of Fools,” Neil Young’s “Everybody Knows This is Nowhere” and Cheap Trick.

A natural raconteur, Costello managed to tell some remarkable stories during his session, though.

A natural raconteur, Costello managed to tell some remarkable stories during his session, though.

Asked once to contribute songs to a young singer’s second album, for example, he said he deferred, thinking a 50 year old’s experience wouldn’t align with that of a 20something. So he wasn’t on Adele’s multi-million selling “21.”

Someone asked if she was an idiot for choosing ”I’ll Wear it Proudly” as a wedding song; he wouldn’t say right out. “The way someone projects themselves into your songs, there’s no way of controlling it.” Along those lines, he said, when someone once told him “I Want You” was the most romantic song she’d ever heard, he told her “You’re in for a powerful amount of pain.”

He never heard a full Led Zeppelin album and still hasn’t heard a full Pink Floyd albums until his twin sons, now 10 stated asking to hear “the viking song.” He bought “Led Zeppelin IV for ‘The Immigrant Song’ but still didn’t like it.

He somewhat regrets his anti-Thatcher song “Tramp the Dirt Down” simply because it’s so strident and single-minded. Most of his songs, he said, have multiple points of view. “I’m distrustful of slogan songs,” he said, “except ‘What’s So Funny About Peace Love and Understanding?’”

He had an intersting history of that song, which he said was written by Nick Lowe for his band Brinsley Schwartz as more as ironic Tin Pan alley-attempt to cash in on the peace movement. Costello’s version was done “as furious as possible” to make another point and now, he noted, Lowe himself plays it solo acoustic with increasing sadness, as its ideals seem further away.

One message song he was proud of was The Specials’ “Free Nelson Mandela,” which he produced in 1983, a time when many people didn’t know South African leader’s name and who Thatcher was still calling a terrorist. Costello wasn’t taking credit for Mandela’s eventual release, but he added, “the song did get people to talk and was part of the process of change.”

He said he recorded his Nashville “Almost Blue,” at a time when he thought country music was better adept in expressing his emotion than anything was writing.

Mining old songs was something many people of the era did not do. “In 1977, a lot of denying there was any music of the past. It was all year zero.” That was until “Joe Strummer started raiding his record collection” for the resulting “London Calling.”

Borrowing from the past was what people did before there was sampling. “You took a riff as a foundation and turned it on its head,” Costello said. “There are only a handful of chords, for heaven’s sake.”

Even so, he didn’t know enough about the music swiping suit between Marvin Gaye’s estate and Robin Thicke about th e latter’s 2013 hit. “I hate to sound like a fogie,” he said, “but I’ve never heard ‘Blurred Lines.’”

Doing a book tour instead of a musical one, though, may have made him feel like an even older fogie.

Just before standing to read a passage about playing the White House in a musical salute to Paul McCartney, Costello said, “I feel just like Dickens without the beard.”

Or as he said in his single song that night, “in a perfect world where everyone was equal / I’d still own the film rights and be working on the sequel.”