The 50th anniversary of Rolling Stone is being marked a number of ways, from a biography that publisher Jann Wenner has already disavowed (and is being well-reviewed) to this two part documentary from Alex Gibney and Blair Foster, “Rolling Stone: Stories from the Edge” (HBO, 9 p.m.) that takes a swing from its heyday.

The 50th anniversary of Rolling Stone is being marked a number of ways, from a biography that publisher Jann Wenner has already disavowed (and is being well-reviewed) to this two part documentary from Alex Gibney and Blair Foster, “Rolling Stone: Stories from the Edge” (HBO, 9 p.m.) that takes a swing from its heyday.

While it isn’t quite clear from the beginning, the approach is episodic, based on individual major stories it’s covered. That isn’t readily apparent until pretty far into a foray into rock ’n’ roll groupies, whose emphasis at first seems pointed at the nudity and sexual content HBO usually offers in series like “The Deuce.” Then it switches to another segment in which a topic is reported in full, from issues that are already memorable.

Wenner’s relationship with John Lennon was crucial to the magazine’s credibility; a picture of him from the set of “How I Won the War” was famously on the first cover in July, 1967. The full length, very frank interview two part with Lennon in 1970, in which he tears away ferociously from his Beatles image would be thought to be the breakthrough. But it actually came earlier, when the magazine agreed to include the nude photos of Lennon and Yoko Ono from the “Two Virgins” album cover that was banned so many places.

The music chosen to back the segments is particularly well chosen, and often played in full. It shows how well it covered the scene in San Francisco, where it was based, but also the political and cultural changes that came with the rock generation.

Where there isn’t footage from interviews, there is text lifted from the magazine and read aloud — oddly, it’s from the familiar voice of Jeff Daniels, which is a little jarring, since he is more closely aligned with a different newsman (also on HBO), Will McAvoy on Aaron Sorkin’s The Newsroom (where he character was more anchorman square than the voice of a generation required here — would Jeff Bridges have been better?).

Daniels takes a break in part one once, when Johnny Depp steps in to narrate the Hunter S. Thompson segment. The actor is an avowed acolyte of the inventor of Gonzo Journalism, so much so that he spent $3 million to shoot Thompson’s ashes into the sky at the writer’s request, at his 2005 funeral.

There is thankfully a trove of Thompson footage and his colorful reporting style, particularly on the campaign trail, where he chronicled the 1972 campaign like no one before. His prose on the surreality of the Nixon vs. McGovern campaign still lives on in memory, particularly his assessment following the landslide election results:

“This may be the year when we finally come face to face with ourselves; finally just lay back and say it — that we are really just a nation of 220 million used car salesmen with all the money we need to buy guns, and no qualms at all about killing anybody else in the world who tries to make us uncomfortable.”

Rolling Stone was the only place where someone like Thompson could be employed, encouraged and celebrated. Though he didn’t make it easy for his editors, particularly on deadline.

When he completely skipped the deadline as Nixon resigned, the magazine used instead the remarkable portfolio from Washington of the event by its ace photographer Annie Leibowitz, who helps move things along by looking at a series of her best known pictures from the magazine with Wenner.

The other journalistic coup for the magazine in the 70s was getting the inside story on Patty Hearst, the kidnapped heiress who had apparently turned revolutionary with her captors. The story had fascinated the country for months, in part because it reflected so many issues about youth, counterculture, revolution and the chasms in America.

Having an interview with Hearst from inside their compound was tantamount to chatting with O.J. while he was on the lam, and yet they were almost scooped when Hearst and crew were arrested just before they could get their issue out. The editors found a way to use the arrest to raise interest in the story.

Whether it was intended or not, the film shows how the rise of punk music reflected Wenner’s initial disinterest with aspects of the rock culture. He was fine with his Beatles and Stones and wasn’t interested in this odd new revolution from New York and London. And while the move from San Francisco to New York in the mid 70s is covered, it isn’t entirely seen how glossy and superficial the publication started to become, as Wenner became obsessed with the Studio 54 party set.

But the end of the hippie dream, the counterculture and any revolution is seen with the murder of John Lennon in 1980.

Rolling Stone was at the center of that tragedy as well; with Leibowitz shooting the iconic cover that ran without words, and Wenner agreeing to Lennon’s last request, that he and Ono be seen together on the cover. The film shows in a way that few places ever did how that death devastated a generation worldwide.

The youthfulness of Wenner when he started is a contrast for his grizzled presence today looking back, but many of his colleagues opt not to be heard but not seen all these years later (something the Stones themselves did on their own 2012 HBO documentary “Crossfire Hurricane”).

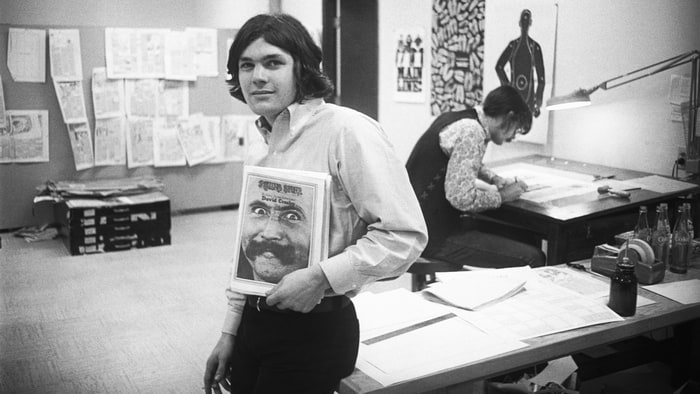

One exception is Cameron Crowe, possibly because he still looks quite young nowadays — and since he first writing for Rolling Stone as a teen, covering the kind of bands that weren’t quite top tier — Deep Purple, Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin, who apparently got a lot of bad reviews initially.

Crowe says he was given his best advice by Wenner when he was advised not to be a fan boy, not to just take a band’s words and run them without analysis or consideration. Wenner then handed him a Joan Didion book as an example.

“Rolling Stone: Stories from the Edge,” produced in part by the magazine itself, tends to give a rosier picture of itself as well. Though there is no way of avoiding in Tuesday’s part two about the 2014 story that nearly did it in — about college rape culture that got it sued.