The death of Charlie Manson this week reminds me of the thwarted artist theory that may have triggered his mania in the first place.

The death of Charlie Manson this week reminds me of the thwarted artist theory that may have triggered his mania in the first place.

Just as Hitler may have been a failed painter who got his revenge on Vienna, Manson may have had his murderous minors storm the mansion where Sharon Tate lived because he thought a record producer who wronged him still lived there.

Like another cult leader years later, David Koresh, Manson recorded an album of his weird songs, one of which was picked up and re-recorded by Guns N’ Roses for its grisly outlaw appeal. An outsider named Brian Hugh Warner named himself Marilyn Manson in part tribute. And just three years ago, some Manson songs made network TV — as part of the soundtrack to the summer David Duchovny period detective series “Aquarius,” alongside songs by Jefferson Airplane and the Doors. And a Manson song charted from one of the most unlikely sources, the Beach Boys.

When Guns N’ Roses added an uncredited “Look to Your Game Girl” on its 1993 album “The Spaghetti Incident?” it caused an outcry from police and others — enough to cause the president of Geffen records, who said “It is certainly not our intent or desire to glorify or enrich anyone who commits heinous and violent crimes.”

For his part, Guns lead singer Axl Rose issued a two-page statement saying “I liked the lyrics and melody of the song” when he first heard it from his brother. Learning it was a Manson song “shocked me,” Rose said, “and I thought there might be other people who would like to hear it.”

His interest was purely sociological, he claimed. “Manson is a dark part of American culture and history. He’s the subject of fear and fascination through books, movies and the interviews he’s done. Most people hadn’t heard anything Charles Manson recorded,” Rose said.

To end the controversy, Rose said he would donating all profits from the track to environmental groups, saying “to what extent Charles Manson is involved in the publishing, I’m not aware.” He indicated an affection for the songwriter, though, with the final words of his statement, “Thanks, Chas.”

Beach Boy drummer Dennis Wilson first met Manson in early 1968, when he picked up a couple of the cult leader’s young female followers who were hitchhiking. According to the account in Steven Gaines’ 1986 book “Heroes and Villians: The True Story of the Beach Boys” (New American Library), Wilson had sex with both of the women, and they invited to Wilson’s house all their sisters and brothers and Manson, the weird leader of their hippie family and an ex-con who was also a part-time songwriter.

![]() That whole summer of 1968, Manson and his followers would hang out at Wilson’s Sunset Boulevard home, leech off his generosity, borrow clothes and fancy cars and eat his food while Wilson was vaguely intrigued with the charisma of the grubby, ex-con philosopher.

That whole summer of 1968, Manson and his followers would hang out at Wilson’s Sunset Boulevard home, leech off his generosity, borrow clothes and fancy cars and eat his food while Wilson was vaguely intrigued with the charisma of the grubby, ex-con philosopher.

Wilson even briefly parroted Manson’s dizzy ideas; for example, he was quoted in a 1968 English rock magazine as saying, “Fear is nothing but awareness.”

“Sometimes the Wizard frightens me,” Wilson said in the interview. “Charlie Manson, who is another friend of mine, says he is God and the devil! He sings, plays and writes poetry…”

The Beach Boys had just started their own label, Brother Records, and Wilson considered Manson a good prospect as a new artist. Besides introducing Manson to his brothers, he introduced him to other friends in the music business, including producer Terry Melcher.

Melcher, the son of Doris Day, thought Manson’s songs had potential and recorded some of them in demo form in a studio and, in 1969, at the Spahn Ranch in the desert, using a film crew. Manson expected Melcher would get him a major record deal.

In the meantime, Manson encouraged the Beach Boys to record one of his songs, with the sole stipulation that none of the lyrics would be changed. One that Dennis Wilson brought to the studio, “Cease To Exist,” had a title echoing Manson’s dark outlook; the song was meant to address the deteriorating relationships among the band.

But Wilson changed the words to “cease to resist,” switched the title to “Never Learn Not To Love” and took full songwriting credit himself.

As sung by Wilson, and begun with a psychedelic-sounding backward cymbal, it was a solidly produced tune that appeared on the Beach Boys’ “20/20” album, their last for Capitol Records. Even with the changes, its lyrics retain the chilling hand of the psychotic murderer: “Give up your world/ Come on and be with me. … Submission is a gift…”

The album and single was released in December 1968, almost a year before the world would know of Manson.

By late 1968, Dennis Wilson had gotten fed up with Manson and his hangers-on and moved out of the rented house where they had become comfortable. As a result, Manson was evicted and moved to his desert compound, where he became obsessed with fears of a coming race riot and the Beatles’ White Album, which served as a lexicon for his warped ideas: “Helter Skelter” as his own bloody skirmish; “Sexie Sadie” as a nickname for his women; “Piggies” for the enemy.

Manson didn’t like the brush-off from Wilson, or from Melcher, so he visited the latter in his home at 10050 Cielo Drive in March 1969.

Melcher had moved out, Manson found, but he met the new occupants — which included film star Sharon Tate, hairdresser Jay Sebring and others.

On Aug. 9, the world was horrified to read of the sadistic massacre of Tate, Sebring and five others in that house, as well as the murder of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca in their home near Griffith Park two days later.

Gaines’ book claims Melcher was “Manson’s real target. The Tate-LaBianca murders were meant only as a warning.”

Could one of the century’s most heinous crimes be blamed on a record deal gone bad? And if so, would Manson’s band look for further revenge against Brian Wilson, who had changed Manson’s lyrics and not given him credit?

Dennis Wilson, for one, was shaken by the news of the murder and his hunch that Manson was behind it, but he didn’t go to the police with it. He later testified that he didn’t remember much about his dealings with Manson. Melcher later testified that he was so horrified, he sought psychiatric care and bodyguards.

Manson was charged with the deaths three months later, when he and his followers were already in custody on car-theft charges and a member of his group bragged about the murders to other cell mates.

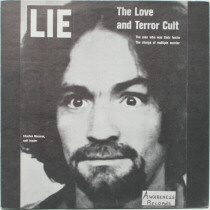

The demonstration tapes Manson recorded with Melcher, which included “Look at Your Game Girl,” first leaked out on Awareness Records in 1970 under the title “Lie.” It was available widely enough that anybody could buy a copy, including Axl Rose’s brother, who bought his, Rose says, “at a large record chain.”

Billboard magazine reported that proceeds to the Manson album “Lie” by Performance Records of New Brunswick, N.J., went to California’s Victims of Violent Crime Fund.

‘’It was not a good record,” colorful rock ’n’ roll figure and longtime roadie Phil Kaufman once said. “I know; I produced it.”

His comments came at a 1994 South by Southwest panel discussion I was covering about Manson, whose moderator called Manson “the original alternative rocker.”

When Kaufman first met Manson, in jail in 1967, “I thought he had a good voice,” Kaufman said. “I thought he sounded like a young Frankie Laine.”

![]()

Kaufman, whose other rock fame came from being one of the two people who stole Gram Parsons’ remains and reburied them in the Joshua Tree Desert after his death in 1973, said he couldn’t get Manson a record deal because ‘’he was completely unmanageable.”

Kaufman claimed never to have made a nickel from the Manson recording, bootleg copies of which came out under the title ‘’Lie.” But he admitted trying to recoup the $3,000 to $4,000 he borrowed to record the original tracks.

‘’You say I’m exploiting him?” he asked one of the 100 people in the SXSW audience. “He tried to kill me four times.”

For one thing, Kaufman lived next door to Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, killed by the Manson gang two days after the massacre at the Tate house.

Attempts to cash in on Manson’s infamy are ‘’hype – and it’s working,” Kaufman said. “Basically, people doing his music are out to make a buck.”

Chief among them, at the panel, was a young, 25-year-old Marilyn Manson before his first album came out, who said his adopted last name was ‘’more about the exploitation of my generation and my exposure to serial killers’ being elevated to celebrity status.”

The young Manson said he recorded his band’s album in the actual Tate house with Trent Reznor because ‘’I wanted to see if there was some kind of vibe there.”

Although too young to remember the crime, Manson claimed there were the same ‘’tensions” in society in the early 90s that there had been 25 years earlier, when the killings shocked the world.

Mostly, he said, ‘’there’s a lot of p.c. propaganda going around that everybody has to love each other – I’m sick of it.”

The way Manson has been portrayed by the media has led to his consideration as just another superstar.

‘’I remember growing up and confusing Jim Morrison with Charles Manson,” Marilyn Manson said.

But he said adulation of Charles Manson – or wearing T-shirts with his picture and the slogan “Charlie Don’t Surf” – were just part of the age – old tradition of kids’ trying to irk parents.

Marilyn Manson’s record career at the time wasn’t getting off to any better a start than did his namesake’s. One record company had already decided not to release his controversial debut.

‘’There is a ray of hope,” the young Manson said, alluding to lessons learned since the ‘60s. ‘’I didn’t get a bunch of my girlfriends together to kill the record executive!”