The venerable guitarist Ry Cooder took a seat to kick off his “Prodigal Son” tour Monday not because he was weary at 71.

The venerable guitarist Ry Cooder took a seat to kick off his “Prodigal Son” tour Monday not because he was weary at 71.

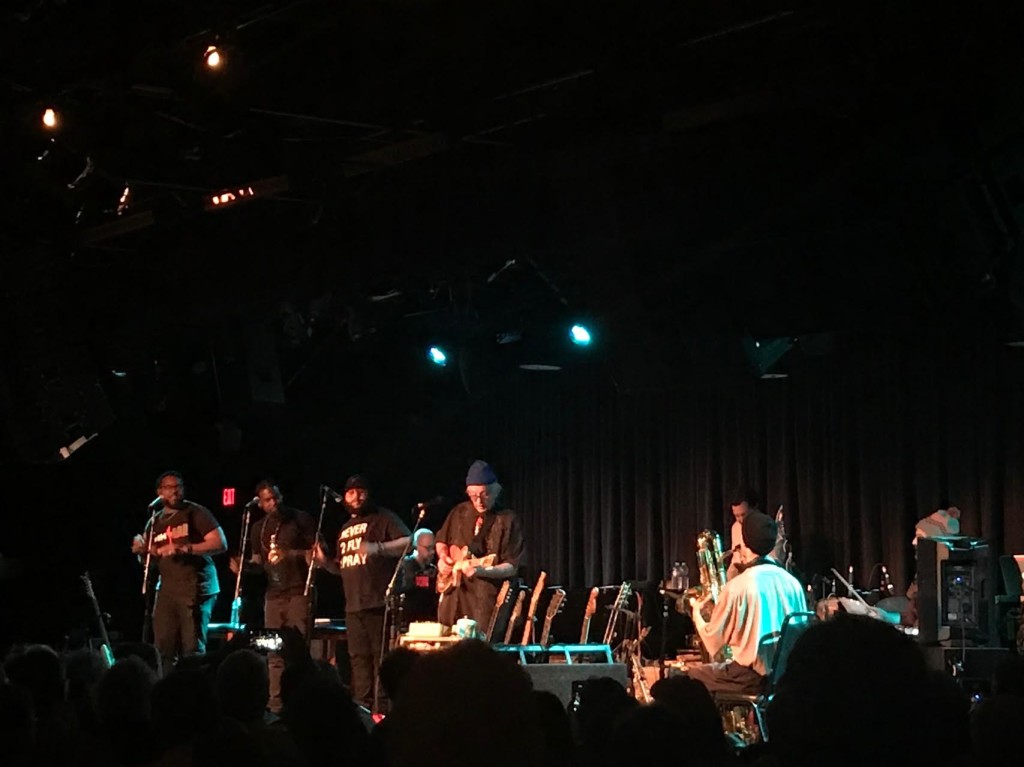

No, he said. Sitting in the direct line of amps arranged in a semi-circle behind him, with a rack of nearly 10 instruments to his side, he found that it all sounded better to him that way.

And it certainly sounded great to the audience as well. For his first solo headlining appearance in the D.C. area in some 37 years, Cooder chose the Birchmere because he liked the place when he played there in the trio with Ricky Skaggs and Sharon White a couple years back. And it certainly was accommodating. As the Southern-most stop on the current tour, it drew a lot of out of towers, who were treated to a large helping of his new album “The Prodigal Son,” but also a few choice oldies from decades back.

Cooder’s slicing guitar has been part of rock history for some time now, from his signature slide in the Rolling Stones’ “Sister Morphine” to gutbucket blues in Captain Beefhearts’s “Safe as Milk”. His sizzling slide set the mood for more than a dozen memorable movies; he won a pair of world music Grammys even before he made “Buena Vista Social Club” and has lately been stewing about politics on more recent releases.

“The Prodigal Son” comes close to some of his earliest solo albums, when he revived the blues songs of long forgotten souls and covered Woody Guthrie. But the work of covering Blind Willie Johnson sounds convincing live, where his voice is lower and more full, matching the indelible slash of electric guitar, whether sweetened with the slide or twanging with depth.

A knit cap on his head and a long grey ponytail trailing down his back, he chose from his oversized rack of vintage guitars, some of which he says he picked like strays from instrument websites, like the double necked item he said might crumble at any minute, on which he only played up one neck.

Cooder doesn’t see himself as a revivalist of classic American music so much as immersed in tunes that carry as much necessary messages for today as they did when written deep in the last century. And as if to drive the point, he’ll add in a striking solo version of “Vigilante Men” a verse about Treyvon Martin, also cut down by a vigilante man Guthrie never knew (but probably imagined).

The intent of old songs like “Everybody Ought to Treat a Stranger,” and “Nobody’s Fault But Mine,’ which which he opened, are timeless, but his own original songs fit right in musically, while dropping modern imagery.

In “Gentrification,” he sings that a “building’s been sold to Johnny Depp” and warns “the Googlemen are coming downtown.” He imagines a heavenly conversation between “Jesus and Woody” (“guess I like sinners better than fascists / and I guess that makes me a dreamer too”). All told, he played eight of the 11 songs on “Prodigal Son.”

He was backed by an effective band that included his son Joachim Cooder on percussion (shunted to the side to make way for the circle of amps), nephew Robert Francis on bass and Sam Gendel on a series of treated horns the provided more of a low, tonal wash.

On the record, Cooder’s own gritty baritone was sweetened by the soulful backing of Arnold McCuller, Bobby King and the late Terry Evans, who died in January at 80. On tour, he is joined by the Hamiltones, a young gospel trio from North Carolina who provided a rush of harmony to several songs and were given a short two-song showcase in the middle of the set.

Because of the approach and musicians on hand, Cooder brought out a few oldies of a similar sound, four of which were from 1979’s “Bop Til You Drop,” in its day the first digitally-recorded major label album in popular music. He didn’t pick his cover of “Little Sister,” which is the closest he got to a radio hit, but “The Very Thing That Makes You Rich” and his version of Arthur Alexander’s “Go Home Girl.” There was also the funk of “Down in Hollywood,” which he said he hadn’t played in 20 years.

And with the Hamitones on hand, he did a couple of doo-wop covers too, The Invincibles’ “I Can’t Win,” which was also from “Bop Til You Drop”, and the Valentino’s “Lookin’ for a Love” (which he recorded live at the “No Nukes” concert in 1979).

Cooder waxed nostalgic about hearing such songs on old R&B shows growing up in Los Angeles. And if he is inspired now, he said, it was in watching old black and white performance clips of gospel greats like the Heavenly Gospel Singers on YouTube. He paused to remember Clarence Fountain of the Blind Boys of Alabama, who died the day before at 88 and he closed with his own gospel benediction, found on his new record, of Blind Alfred Reed’s “You Must Unload.”

To open, Joachim Cooper stepped out front to sing a handful of songs from his new EP “Fuchsia Machu Picchu,” setting percussion going with a loop before singing and mostly playing a melodic, ringing elongated Africa thumb piano he jerryrigged himself called a array mbira, backed by Francis and Gendel. It was a wondrously spacey sound, reflecting a life growing up in the heady world music brew his father had ventured into.

The setlist for Ry Cooder Monday was:

- “Nobody’s Fault But Mine”

- “Shrinking Man”

- “Gentrification”

- “Everybody Ought to Treat a Stranger Right”

- “Go Home Girl”

- “The Very Thing That Makes You Rich”

- “Vigilante Man”

- “Jesus and Woody”

- “Lookin’ for a Love”

- “Down in Hollywood”

- “The Prodigal Son”

- “I Can’t Win”

- “You Must Unload”