Charley Pride is a singular story in country music.

Charley Pride is a singular story in country music.

Subject of a new black History Month “American Masters” (PBS, 9 p.m., check local listings), the focus of “Charley Pride; I’m Just Me” is not the first African-American in country music (that would be Grand Ole Opry harmonica cat DeFord Bailey). But he is arguably the first black country superstar, with more than 50 Top 10 country singles, 40 of which went to No. 1. A three-time Grammy winner, he got the lifetime achievement award two years ago.

The son of a sharecropper, he came to music only after a stint in the Negro Leagues and failing to be signed by the majors.

“There was a certain point where things are not for you and I think that was part of it,” he told me of his baseball efforts.

While up playing minor league ball in Montana, he started appearing on stages singing the old country songs he heard on the radio in Mississippi. He recalled a neighbor there who told him: ““Have you ever thought you’re not on this planet to play baseball, you’re on this planet to sing.” So, he said, “after all these years, I finally accepted it.”

Part of his success came in not addressing the color of his skin, which was an issue in parts of the country where country music was possible.

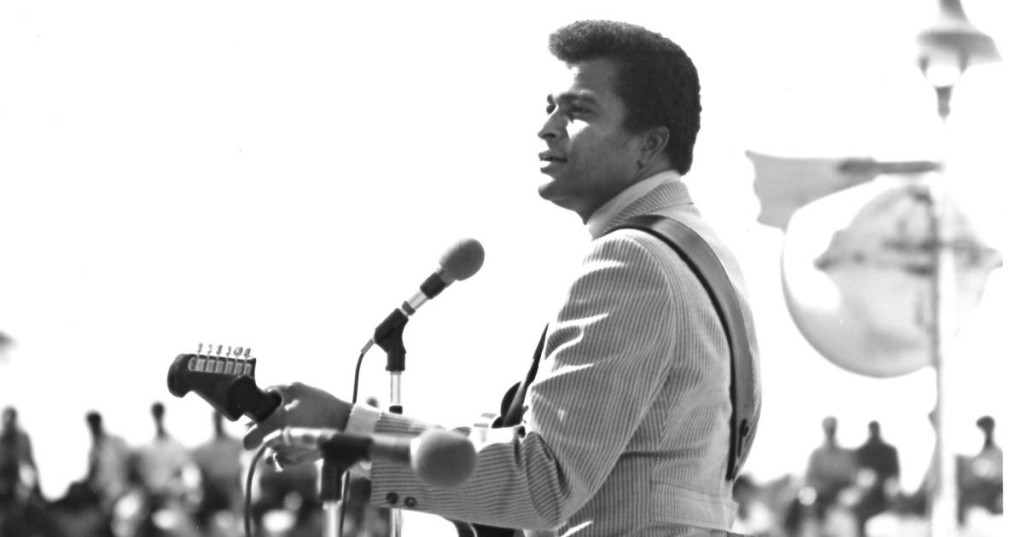

At the TV Critics Association winter press tour, Pride, who turns 81 next month, talked about opening a big package tour for Ralph Emery in 1966, when people knew his hits but maybe didn’t know what he looked like.

Getting a startled reaction early in the tour, he recalled, he would announce, ““Ladies and gentlemen, I realize it’s a very unique, me coming out here on a country music show having this permanent tan,” he said. “I ain’t got time to talk about our pigments. I got only 10 minutes. I’m going to do my three songs. And if I have time, I’ll do maybe a Hank Williams song.”

It all worked out OK and even included a big crossover hit in 1971, “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin.’”

He may have been a trailblazer for African-American country singers who followed him, such as Darius Rucker and Jimmie Allen (who both extol his qualities in the documentary).

But, Pride told me later, “I didn’t go into this business to do that, like Jackie Robinson did. There’s a difference there.”

“My thing was it wasn’t about all of this,” he said, pointing to his skin. “Once I come out and start singing, it didn’t make any difference whether I was pink. They wanted to hear me sing again. So that’s the way my career has been all these years.”