Merce Cunningham’s legacy lingers in contemporary dance, and avant-garde collaboration. He eliminated storylines in dance pieces, concentrated on movement as pointed as abstract art and vaulted modernist music (particularly that of his partner John Cage) to wide popularity.

Merce Cunningham’s legacy lingers in contemporary dance, and avant-garde collaboration. He eliminated storylines in dance pieces, concentrated on movement as pointed as abstract art and vaulted modernist music (particularly that of his partner John Cage) to wide popularity.

His 50 year presence in the dance world guaranteed his influence continue long after his death a decade ago at 90. So to mark the centenary of his birth, Kennedy Center has devised a weekend’s celebration, capped by two reconstructed performances he created.

“Beach Birds,” from 1991, and “BIPED” from 1999 were performed by the Compagnie Centre National de Danse Contamporaine-Angers. It is a French company, where the artistic director since 2013 has been Robert Swinston, a 30-year member of Cunningham’s company who has reconstructed the two pieces in which he once danced.

The striking “Beach Birds” features 11 dancers, whose white leotards and black arm and shoulder coverings and gloves have them resemble a flock of penguins, while emphasizing the jutting, angular, inventive movements of the arms and hands.

In their various groupings, the dancers never quite do things together, similar to birds — one moves, and the next one does, and so on. Yet there is a kind of fluid unison in that they are all creating movements that have a singular effect.

They move and flutter to the music of Cage and his “Four3,” a piece for piano, a violin playing a high C, and rainsticks, that instrument devised by indigenous people of South America, where the movement approximates a gentle shower. The piano pieces are a set of 12 chance-determined Cage variations on Erik Satie’s “Vexations,” and so change every time. And there is silence along with the scree of the string.

The music works independent of the movement — all the Cunningham rehearsals are done to silence. Yet they seemed to work together to replicate a bird’s day on an empty beach. Martha Skinner, who designed the lighting as well as the marvelous costumes, has the lights subtly change through the piece on the stark stage, as if from dawn to dusk.

Certainly, there is a clearer view of the dancers for “Beach Birds” than there is for “BIPED,” performed entirely behind a scrim. That adds a gauziness to the proceedings — and also lends surprise when dancers suddenly appear from behind black curtained-spaces at the rear of the stage.

But the scrim also serves as a screen on which to project lines and dots and sometimes motion-captured dance movements. It gives a dimension to the scene as well as context of fuzzy, moving abstraction.

Cunningham wrote that it is meant to replicate “the feeling of switching channels on the TV.” (And viewers not able to watch postseason baseball because of the performance Thursday may have felt like reaching for the remote).

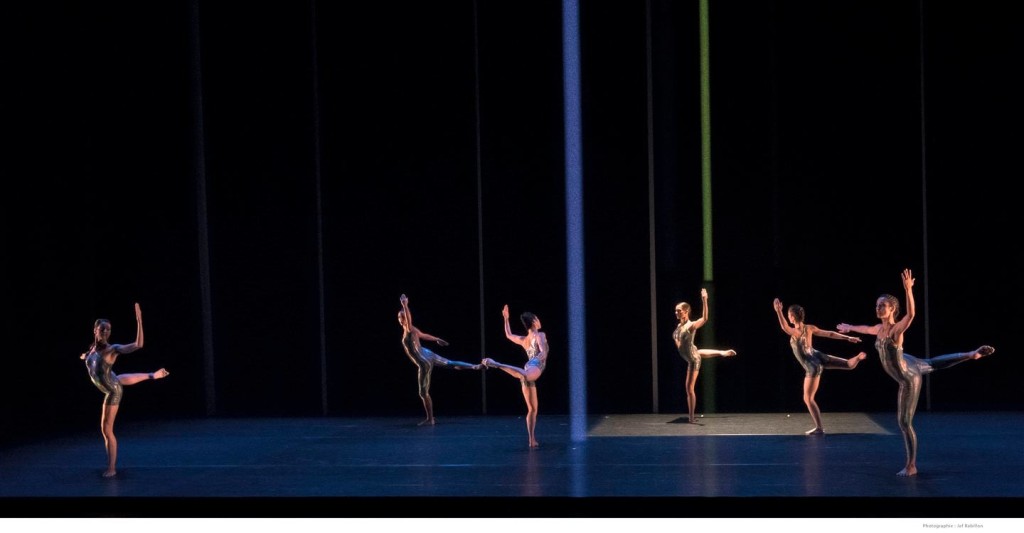

Suzanne Gallo’s costumes were glittery jumpsuits that seemed from a disco era, but the projected dance figures from motion capture seemed even more dated somehow. It seemed to be celebrating a computer interaction that was then-new but now seems quaint (and unnecessary).

The choreography also relied on computer software done in solos, duets, trios and ensembles though it retained a humanness that kept it from seeming robotic. Even the music was part recorded, part live with a quartet that included the inventive English composer of the piece, Gavin Bryars, on double bass.

While the performances were conducted in the Eisenhower Theatre, the Kennedy Center’s “Merce Cunningham at 100” celebration provided an opportunity to use the innovative spaces of its recently opened REACH spaces, with films of past Cunningham dances on its plaza video wall, a panel discussion in one of the meeting rooms, and a recreation of Andy Warhol’s “Silver Clouds” installation in another room, where dozens of large, silvery, pillow-shaped Mylar balloons were available to be batted up to the high ceilings. Cunningham had incorporated the piece into his 1968 work “RainForest.”

The commemoration kicked off delightfully Wednesday night in the REACH Skylight Pavilion with a concert by Margaret Leng Tan, “John Cage: Music for Merce,” that was as much a demonstration of modernism as it was a collection of ringing examples the composer had made for the choreographer.

It included works on a Steinway piano, during which she’d stand and swipe the strings inside for effect, and others on “prepared” piano, whose strings were deadened, rung, or enhanced by a series of screws, nails, clothespins and putty that were painstakingly placed to bring completely different army of sounds to the pieces becoming more percussive and ringing (one screw had a washer that danced upward, making a tambourine-like sound.

Tan’s expertise, though, is with that of a toy piano. So with a child’s sized Schoenhut that she moved around stage, she pinged out some unique pieces such as Cage’s “Suite for Toy Piano.”

She had to semi-squat on the child-sized stool to make its nine notes soar. For another, she placed the toy instrument on a platform for the even more musical “Dream,” which shared the themes on the full and toy versions of the piano — like an adult and child duet.

The revelation may have been Cage’s “In the Name of the Holocaust” that he wrote for Cunningham in 1942, using the prepared piano for darker themes. The honoree would have also been absorbed in its sober tones.