At the Metro there were all kinds of costumed plushy characters, enough to make you think there was a convention at the nearby Marriott. But it had nothing to do with the Small Press Expo — the SPX — that I was catching a train to see in Bethesda.

At the Metro there were all kinds of costumed plushy characters, enough to make you think there was a convention at the nearby Marriott. But it had nothing to do with the Small Press Expo — the SPX — that I was catching a train to see in Bethesda.

Unlike most all ComicCons where fans where their enthusiasm on their costumes (and there is a whole reality show now about costly), SPX is the home instead of (comparatively) serious graphic novels, comics for adults and the establishment underground.

Last year’s event, my first, was an amazing collection of people that included Dan Clowes, Chris Ware and the Hernandez brothers — all prominent in my graphic novel and comics collection.

This year was good too, with people from Seth to Peter Bagge. But beyond the big names there were tables and tables of comic artists and small presses with their goods. Just about everything looked interesting, intriguingly designed with just the right color palettes. The other common element: No superheroes.

If you haven’t quite outgrown capes, than this wasn’t the place for you (hence the lack of costumed fans). But for others who’ve followed the serious marriage of image and words into an art form that still isn’t quite taken completely seriously, this was the place to be, where all the people attending seemed interesting too.

But as much as these people seem like stars (with the imagined success stories tied to them), it was enlightening to chat to Adrian Tomine, who has created more than a dozen issues of Optic Nerve and is known to a whole other audience as a standout illustrator at The New Yorker, who happened, in fact, to have done this week’s cover.

I talked to him whether he’d gotten a lot of offers to turn his books into movies, since they’re cinematic and have that kind of honest ennui one finds in youthful mumblecore indie projects.

He has meetings and is frankly tempted by the money. For all his success, it hasn’t been enough to buy a house or start saving for his daughter to go to college. But Hollywood hasn’t been good to graphic novelists so far.

“For every ‘Ghost World,’ there’s an ‘Art School Confidential,'” I said, mentioning two wildly divergent Clowes projects on film.

“You said it, not me,” Tomine said.

But even though graphic novels look like completed storyboards, film people rarely pick up on their nuances (“American Splendor” might have been another exception).

Still, decades after Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” made the form respectable, there still seems little serious attention to the form, such that graphic depictions of history that emerged at this year’s event still needed a wider audience.

Peter Bagge, who earned his name with years of wild comics under the title “Hate,” spent a year researching the life of Margaret Sanger to present his new work on her life. And though he still uses his same style of rubbery tube arms and cartoon expressions, he tried to include details of her life missing from other biographies in a panel presentation called “Beyond Hate.”

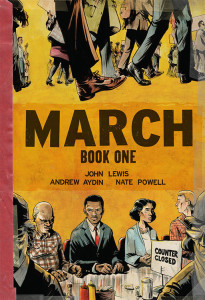

History itself was part of the making of another graphic novel this fall, “The March: Book One” that depicts Civil Rights struggles from the point of view of now Congressman John Lewis. Three weeks ago, he spoke to tens of thousands at the Lincoln Memorial as the only surviving major speaker from the 1963 March on Washington. Saturday, he spoke to a room of 100 or so on retelling that tale for a comics audience.

It was his staffer Andrew Aydin, an admitted comics guy, who had talked him into doing the project illustrated by Nate Powell. he had done his graduate study on a widely distributed 1958 comic on Martin Luther King, that had a direct affect on two of the Greenboro Four who sat defiantly at a Woolworth counter and continues to have an affect on nonviolent uprisings in other parts of the world.

It’s the kind of effect kids in furry costumes will never have.