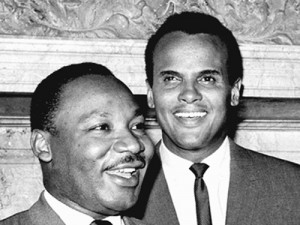

The day after the memorial to Martin Luther King was officially dedicated in Washington comes the story of the singer and humanitarian who was by his side as the battle for civil rights was being fought.

The day after the memorial to Martin Luther King was officially dedicated in Washington comes the story of the singer and humanitarian who was by his side as the battle for civil rights was being fought.

King himself once said of Harry Belafonte, that his popularity “and his commitment to our cause is a key ingredient to the global struggle for freedom and a powerful tactical weapon in the civil rights movement in America.”

When Paul Robeson heard him sing early in his career, he counseled Belafonte, “Get them to sing our song and they will want to know who you are.”

They were still singing his first hit song, “Banana Boat (Day-O)” during the league championships in baseball last week and they’ll probably be singing it in the stands during the World Series later this week.

He sold a million copies of his album “Calypso” and introduced the music to the United States. A musical giant who was the first black man to win an Emmy for producing his own special, he’s also been blacklisted, harassed and spied on by government, targeted by the Klan and casino bosses alike. Though his voice is rather raspy, he’s got quite a tale to tell.

And others, including Tony Bennett, Ruby Dee, Coretta Scott King, Miriam Makeba, Nelson Mandela and Sidney Poiter help tell it in Susan Rostock’s documentary “Sing Your Song” (HBO, 10 p.m.), a festival award winner making its premiere tonight.

Belafonte told reporters at the TV Critics Association summer press tour that he had long avoided putting his life on film in fear of self-aggrandizement. But now that he has, he said, “My primary interest, really, is not only that the film be successful, not so much from what it will give me in any financial return. That’s the least of my interests. I say that cautiously, understanding that others have that as not the least of their interests. However, what I do need to have happen is that in a world that is askew as this one is, in a country that is as lost as it is both from the absence of a clear sense of moral purpose and lives in a place of straight political upheaval, that perhaps this film, as a representative of thousands of other stories, can tell about a time when we faced dilemmas and we faced problems and the kind of moral forces that rose out of our community to try to make a difference.”

So far so good, he said. “Those people who have seen this film in the places we have shown it in the private sector, the people of communities and to young men in prison and young men in communities where gangs reign and in universities and other places, have been more than it’s been more than rewarding for us that they felt not only excited by what they saw, but saw that it helped them find a purpose of how they could perhaps use their own lives.”

Still active at 70, he was asked about the impasses in Washington that have dominated the news.

“My question would be to the Congress and to the President and to a lot of institutions in the United States of power, ‘What happened to moral truth? What happened to moral courage? Why has it been so eliminated from our DNA? Why is it so unattainable in our current social quest and where we go?’

“I understand the game of politics,” he said. “I’ve been at it for 70 years. Oh, wow. But politics without moral purpose, really, more often than not, winds up winds up as tyranny, and I think the more we capitulate to what is practical, what is more easily achieved in the face of what may be more difficult to do but necessary, I think is where we sit. Barack Obama and his mission has failed because it has lacked a certain kind of moral courage, a certain kind of moral vision that we are in need of.

“This does not make him a stand-alone, however, and there is still a lot of opportunity for that corner to be turned,” Belafonte says. “I think, if anything, what the artists should be doing and what the world at large should be doing should be a campaign to make him do it. Once in a story told in the film, Eleanor Roosevelt, who was a mentor, had invited a man by the name of A. Philip Randolph to come visit the White House and to tell her husband how he saw the union and what he thought of the plight of Negroes and of the labor movement because he was the labor leader. And after he held forth, at the end of his point of view, Roosevelt said, ‘Well, Mr. Randolph, I have to tell you, I’m most appreciative of your point of view, and I agree with almost everything you have said, if not all of it, and I will I agree that I have failed to use my platform as fully as I could and will in the services that you feel you are in need of. But I would ask one thing of you. If I go to do this, I would like to be motivated by the fact that you went out and made me do it.’

“And I think in a lifetime where I have been a political social activist, it is what we made the government do, not what the government did voluntarily. It was what we made happen in the time of America in the ’50s and ’60s, even before then, when the nation decided to go to war against fascism, et cetera, et cetera.

“But I think where we have capitulated — most of the institutions of this country have capitulated — is that it does not feel any need or any passion or any desire to go out and force the institution of power and legislation and all of that stuff to come to grips with what they are denying us. I think that that was part of what was invested in Barack Obama. When he said, “Yes, we can,” it may have been politically clever. He never defined he never defined for us what he said what was it he was saying? Yes, we can do? So those of us who felt that we needed change filled in that space with our own images of what we thought he meant only to find out we are all disappointed because none of those things have been satisfied.”

[…]very few websites that happen to be detailed below, from our point of view are undoubtedly well worth checking out[…]……

[…]Here is a Great Blog You Might Find Interesting that we Encourage You[…]……