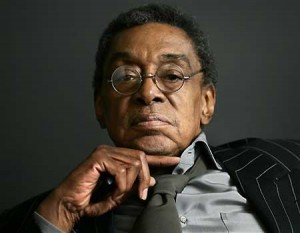

Sad to hear of the death at 75 of Don Cornelius, the host and creator of “Soul Train,” a show so cool and lasting, it was still playing this evening on a local station opposite national newscasts’ attempts to explain its legacy.

Sad to hear of the death at 75 of Don Cornelius, the host and creator of “Soul Train,” a show so cool and lasting, it was still playing this evening on a local station opposite national newscasts’ attempts to explain its legacy.

Cornelius was the opposite of Dick Clark – laconic, elegant, cool. It was his “Soul Train” that was TV’s longest-running R&B showcase. More than that, it was a place where African-Americans could see themselves on the screen (after an era of TV dance segregation epitomized in “Hairspray”).

And besides the string of classic performers who made the stop on the show, there was also the groundbreaking moves of the Soul Train Line – the starting point for every hip-hop move on “So You Think You Can Dance” or “America’s Best Dance Crew.”

I spoke to Cornelius about 1995 when it was time for a 25th anniversary special for “Soul Train” that would include some of the superstars who were on his show, including such luminaries as Stevie Wonder.

“Stevie came on in the early ’70s, shortly after the show first caught hold as a nationally syndicated show,” Cornelius said. “It was one of the highlights of my career.”

“Like any show when it’s new, the major stars tend to not rush to appear on it. You don’t really know you’ve arrived or you’re arriving until you see people like Aretha Franklin, James Brown and Stevie Wonder appearing. So it took several years before we’d see people like that.”

And such high-wattage stars decided to play “Soul Train” “mostly as a result of their kids watching the show, and their own kids saying, ‘Mama, when are you going to do that “Soul Train” show?’ Kids were really plugging into that show, and we were able to make it without major stars. The tendency is to say `Let’s see how this goes before I put my career on the line.’ ”

The single exception to this rule was Gladys Knight, Cornelius said. Her agreeing to be on the pilot of the small-scale local dance show ensured that the pilot in fact became the first episode.

“She was an established star we were able to build the first show around, the first star that gave us the impetus to sell it.”

“Soul Train” was a local Chicago show for just one year before it was syndicated to 15 markets the next year. At its peak, “Soul Train” and its influential features like the line dance, were seen in 100 markets nationally; by he time I spoke to him, with the show produced in Los Angeles, it had settled down to about 80.

But despite all the changes in television over the years, and the proliferation of channels that cable TV has brought, things hadn’t changed much, Cornelius said.

“I don’t see the airwaves becoming saturated” with programming for African-Americans, he said. “In fact, I see it going the opposite direction. That’s notwithstanding the black sitcom, which is not really there yet.”

In such an atmosphere, how did “Soul Train” last to become not only the longest-running show in syndication, but the only currently running dance show in the 1990?

“There’s a built-in benefit based on the music on which it is based,” Cornelius said. “Any show based on soul music will stay popular as long as the music stays popular. A show like `American Bandstand’ could stay as popular as long as pop music stayed popular. But there were other reasons ‘Bandstand’ didn’t survive.

“While we can’t take any credit for doing anything extra special, we didn’t make any mistakes.”

Part of the downfall of “Bandstand,” Cornelius said, was its growing dependence on the new field of music videos, which diluted its commitment to being a dance music show.

While “video is fascinating to some,” he said, “it would never replace live action.”

Similarly, “Soul Train” never strongly embraced other passing fancies. “We never went out of our way to become a disco format, versus a soul-music format that played disco records if they were soulful. It’s a matter of maintaining an identity that will keep you on track.”

Like most R & B radio stations, “Soul Train” has had a greater struggle maintaining an identity during the rise of rap.

“There again you have to have a certain identity,” he said, “if one intends not to flop around like a dishrag.

“”We have some differences with the way African-American-oriented music is going. We don’t have a gangsta rap policy,” he said, “but there are certain messages you just won’t hear on `Soul Train.’

“Just like some R & B records are great and some are dogs, some rap records are great and some are dogs,” Cornelius said. “People who are deeply into rap think all rap records are great records. But that is not the case. That’s one area where we differ.”